By Vivien Pailas

Imagine having to make a choice between your career or job and staying at home to look after a young child because it just doesn’t make financial sense to work? This is the reality of many family’s with young children in the UK and the sheer impact of this is far reaching.

Recent statistics from the OECD shows that the UK has the second most expensive childcare system in the world. If that statistic wasn’t depressing enough, since 2009 prices have increased by 27%, making childcare more expensive than ever before.

Any working family in the UK with a young child knows the struggle. Finding good quality and affordable childcare is challenging enough, but for many families it simply doesn’t make sense for both parents to work as the high cost of childcare means it’s not a viable option. Throw two young children into the mix and it’s nearly impossible for some.

As a freelancer myself, I know this struggle first hand. The instability of freelance work means there are some months where I’m barely covering the cost of childcare. I love my work and I’m lucky I have a partner cover these costs in those slow months, but the struggle is real. You see when one parent drops out of the workforce, in most cases, it’s the mother, propelling the gender pay gap and the motherhood penalty.

For families who are not in work, have lost jobs or are in education, it’s seemingly impossible. As Dr Jana Javornik, an academic who has written extensively on this topic, and Associate Professor at the University of Leeds states, ‘in the UK, state-funded help for childcare is tied to being in work. This suggests that the government sees childcare largely as a support strategy for employed parents. But for parents in education, training, seeking a job or starting a business, having quality childcare in place is essential before they can undertake these activities.’

Ensuring childcare is not only accessible but adequate enough is good for everyone and has a positive impact on women, children, families and society as whole. So why isn’t the government doing more to address this?

The OECD looked into the costs of childcare around the world and found some wide-ranging differences in how much people pay. We decided to look to our Nordic neighbours, who seem to get it right when it comes to childcare, and find out what they earn and spend on childcare vs. families in the UK and our findings were astounding.

Randi – Denmark

I work in a church 30 hours a week, I’m the Culture and Communications Manager there. I have 2 children, a boy 6 years and a girl 3 years and I’ve been married for 9 years. We live in the outer part of Copenhagen in an area called Bronshoj.

I work 5 days a week, 6 hours a day and I work for 30 hours a week on average. Every hour that I work more than 30 hours I can use it to take time off, when I need to, or in the more quiet periods of the year. It’s my choice to work five short days. I work from 9am to 3pm and on days when the family needs it, come in at other hours. I have complete flexibility in my hours, as long as do my job. I am also allowed to work from home when I want to.

Our combined income is approx. £6,400 after taxes. Our rent is £616 per month and we spend about £900 on all other household expenses and we pay £260 for childcare. After we deduct all of our expenses we have approx. £4,600 per month left over.

Bjarney- Iceland

I´m 40 years old and I live in Reykjavik, Iceland. I have a son who just turned six and I’m a single parent. I have a degree in Sports Science and work as an primary school teacher 8 hours a day, 5 days a week. I have side job as a personal trainer and train 4 hours a week in the afternoon.

My monthly income plus child support and compensation (the government also subsidises if you´re renting), is about £3,400 per month and my expenses are about £2,200 (including my rent which is £1,200 per month). In Iceland the government subsidises childcare so I pay about £120 per month for daycare 8 hours a day, 5 days of the week.

I used to live in the UK and the main reason I left is because I could not make ends meet as a single parent, mainly because of the childcare system, I just couldn´t afford it. Not with my salary at the time and other expenses.

Living in Iceland means I have managed to save up for a down payment on my own home and that would never have been possible in the UK as single parent. It’s such a huge gender equality issue, in Iceland I can be independent, look after myself and my son and provide us a good life. That’s so important and valuable.

Caroline – UK

I live in North London with my partner Josh and our son Caleb who is nearly 2. My partner Josh and I work full time, I work 9.30am to 6pm Monday to Friday as a partnerships coordinator, and Josh works as a PCSO for the British transport police. As Josh is part of the BTP he works shifts, meaning he looks after Caleb on some days so he’s not with his childminder full time. Our average household expenses including rent, bills and food is roughly £1,986, we then have other expenses (student loans, bills travel etc) which is approx. £800 per month. For childcare we are lucky enough to get childcare vouchers, which are £220 a month. However these are taken off josh’s pay before tax meaning he is taxed at a lower rate. Whilst it does help we do still lose money off his pay for it. On average we then need to put another £200-300 into child-care per month. So our outgoing expenses are nearly £3K and our joint income per month is around £3,071 after tax. Due to strict budgeting we have actually managed to find some spare money to save. However this is not enough to afford to save for a house or holidays, it goes on birthdays and Christmas.

To highlight the importance of this, if Josh did not work shifts work we would not be able to afford childcare. In September Josh should be under going PC training for 16 weeks which means Caleb will be at his childminders full time. Due to this I’m currently in negotiations about working 1 or 2 days from home to help with the cost. However this is not going well and we are considering getting a loan to help with the cost of childcare for the first month whilst wewait for our income to go up due to josh’s pay rise.

It’s important to stress that we can only afford to live and work full time due to Calebs part time child care hours.If we both worked full time we would not be able to afford full time child-care.

Francis – UK (not her real name)

I’m a 36 year old mum of two, aged 14 months and 3 years, and I currently work in IT in the south of England. Childcare costs are currently making my job have nearly zero financial value and as of the end of next month, I’m planning to terminate my employment as I can’t cover the costs for the school holidays.

I’m not prepared to pay to go to work which is approx £400 more than I’d earn. I’ve got the added complication of planning a career change to Adult nursing, which due to childcare costs is proving complicated too. I’m currently working 3 days per week (24 hours). Our monthly out goings including child-care are approx £2,850 and our household income each month is £3,075. Our average child-care costs per month is around £650 but this can vary depending on how many days fall into that month. This includes the 30 hours of funding that my daughter receives.

So what can be done about this? According to Dr Jana Javornik we really need to look to our Nordic neighbours who have a ‘demand led’ system of childcare. Their approach to universal childcare means governments invest heavily in childcare infrastructure so fee’s are means tested, heavily subsidised and even waived for those that can’t afford it. This means both parents can go back to work and not worry about how to make ends meet if they do so.

Dr Jana Javornik adds, ‘Childcare in the UK has been among the most expensive in the world for a very long time. Other countries, including some of the Nordic states and Slovenia have a simple system of a sliding fee scale for both daycare and after-school care that is based on parents’ income. There, supporting parents to raise the next generation is seen as a social investment in future generations, improving their chances in life to lead a life they have reason to value.’

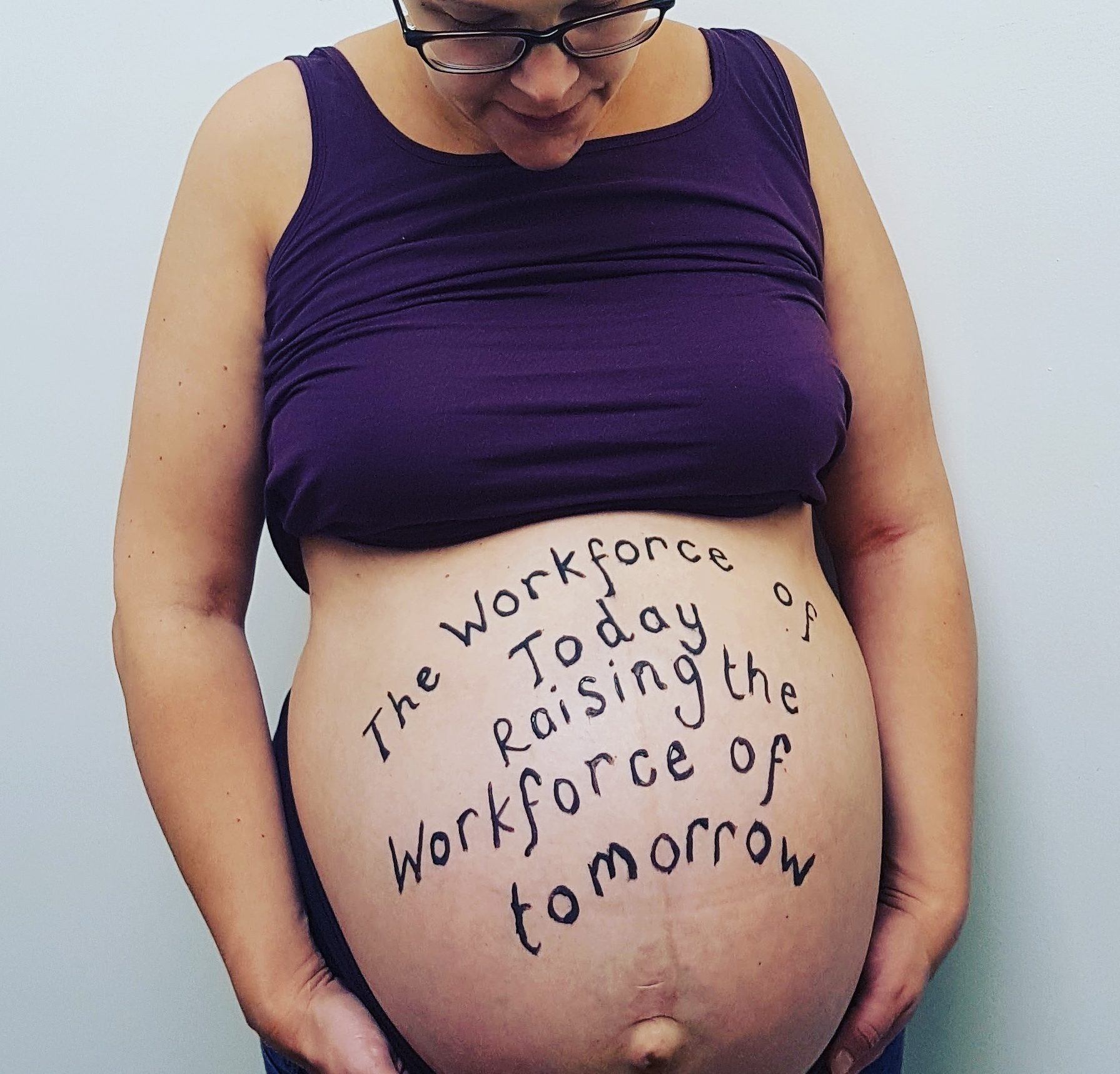

Work is such an important part of our lives and our identity. It’s a source of financial security and independence and for many mothers like me, a place where they can regain their confidence after being cut off from the professional world whilst being on maternity leave.

Of course it is a choice, but one that shouldn’t be governed by our costly childcare system. When returning to work, mothers need all the support they can get, and our government needs to do more to support this. If the Nordics can do it surely we can!

Vivien Pailas